Feb 06, 2026

Feb 06, 2026

An Indo-Mauritian girl out to reconstruct her own narrative and world

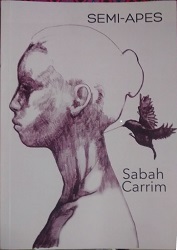

Sabah Carrim | Semi-Apes | Novel | 108 Publishing, Kuala Lumpur. 2015 | ISBN 9789671107416 | Pages 293 | For copies: Amazon India

Semi-Apes, set in a Mauritian town, is the story of a girl brought up in cloistered, conservative and conflicting confines, who resolves to leave the country once for all, and reconstruct her own narrative and world. Scholarship is her only chance since her father doesn’t provide for her overseas education unlike for her brothers, in a discriminating religious milieu of primacy to the sons. When Heera eventually flies to London, she does so with a millstone of none-too-happy and traumatising experiences. Everything that goes into her psyche is delineated with a clinical analysis by Sabah Carrim, the writer who has launched her novel in several countries. A Mauritian of Indian origin, and a former law lecturer currently living in Kuala Lumpur and doing her doctorate on War Crimes Tribunals, her earlier novel “Humeirah” too has a Mauritian backdrop.

Semi-Apes, set in a Mauritian town, is the story of a girl brought up in cloistered, conservative and conflicting confines, who resolves to leave the country once for all, and reconstruct her own narrative and world. Scholarship is her only chance since her father doesn’t provide for her overseas education unlike for her brothers, in a discriminating religious milieu of primacy to the sons. When Heera eventually flies to London, she does so with a millstone of none-too-happy and traumatising experiences. Everything that goes into her psyche is delineated with a clinical analysis by Sabah Carrim, the writer who has launched her novel in several countries. A Mauritian of Indian origin, and a former law lecturer currently living in Kuala Lumpur and doing her doctorate on War Crimes Tribunals, her earlier novel “Humeirah” too has a Mauritian backdrop.

Though sandwiched between her mom’s incorrigible termagancy and dad’s intellectual dictatorship, and despite her brush with madarsa learning which offers just abstract, invisible and Hereafter things, Heera the protagonist gets attracted, like any other child, to modern school education for tangible benefits and future, and to Judeo-Christian values and Freudian religion. Her father, an academic, is averse to any socialising because of the shallow conversations, undignified humour and non-ideational but personalities-centric discussions going into them. And he detests the weekend invites since weekends are strictly meant for the family. Such type of social secession leads the members to seismically react even to minor inconveniences like “a leaking fridge, an overgrown hedge or a burnt light bulb,” remarks Heera. Paradoxically, the sharp internecine differences within the family make the self-chosen in-camera life claustrophobic, even as their general unacceptability al fresco turns them agoraphobic as well. Attempts to sneak out of such tenebrous atmosphere have their own pitfalls of turning the girls into unsuspecting victims of paedophilia and even incest.

By virtue of her constant introspection and critical and eclectic enquiry, Heera questions how she can ignore “the remainder of five-and-a-half billion” non-Muslims if she were to lap up the belief of the “religious zealots” that the Sunnis are blessed for not being “born as an animal, or as a non-Muslim, or as a Shi’a Muslim.”

In her quest for a life of her own devoid of any debilitating trappings, Heera dissects people and things with her analytical acumen. The hallmark of a cultured mind is stretching of the mind with “deepest thoughts and emotions” which can be nurtured only by reading the right books and not the daily newsy sensations. Journos with their know-all cockiness and superficial savvy dish out stories that make us raucously disturbed, restless and frustrated against the government and its policies. She has also a dig at the daily Hindi TV serials that thrive on bizarre themes and wily characters. Instead, she prefers books for they can fire your imagination and “extend your thoughts as far as you want.”

Heera the clinical psychologist doesn’t spare even her own profession which – according to her, founded on fundamental misconceptions – has turned into a fetish – to offer superficial, make-believe palliatives to the patients. These shrinks gloat over and hide behind scientific terminology which gives a euphoric boost to their own egos but hardly helps the patients who more than anything else need empathy, while strong-willed people don’t need psychiatry at all. All the same, the subject has helped Heera to probe her own mind.

Apart from the interesting pen-portraits of the members of Heera’s family and the small circle of her kith and kin, we are treated to stimulating truisms and reflections, like: “… it is negativity that has been the catalyst for all the goodness in the world,” for anxiety is conducive to one’s good performance in an exam or competition; and “Ideally, every question should end with another question, or put in a simple way, every answer should be open-ended,” because nobody is omniscient, so much so “at least it stops us from being arrogant” and “makes us humble.”

And it is not concepts like truth, justice, and fairness that win in the courts but the Machiavellian tactics of the unscrupulous but influential lawyers. Whether Heera would ultimately achieve her goals, and who constitute the semi-apes… to know this, one should course through the novel.

(Originally published in The Hans India daily, Jan 3, 2016)

03-Jan-2016

More by : U Atreya Sarma