Feb 16, 2026

Feb 16, 2026

Director: Yasujiro Ozu/ Japan/Japanese/134 mts

When dealing with a master like Ozu it's splitting hairs to assign varying degrees of greatness to his individual films, and, quite frankly, such laurels mean nothing—especially when considering Ozu's films are so completely committed to avoiding the grandiosity such ready-made labels imply. Ozu, often called "the most Japanese of Japanese filmmakers," made films about everyday life. His is a cinema of cumulative impact. His characters are usually middle-class folks not overly concerned with money, and not subject to but actively a part of daily rituals that some may find mundane but are truly the stuff of life: having a cordial, if superficial, conversation with a neighbor; preparing the morning breakfast; folding laundry; rearranging furniture to make room for company; packing for a trip.

Tokyo Story's plot couldn't be simpler. An aging couple, Hirayama Shukichi and his wife, Tomi living in retirement in the port city of Onomichi, prepare for a train trip to Tokyo to visit their children. A stopover to see a son in Osaka is to be followed by a stay with their eldest son, Koichi, a doctor. Their quiet preparations and gentle banter set tone of conteplation and nostagia. Once in Tokyo, however, they realize that Koichi, living in a poor suburb and with a small paediatric practice, is hardly the success they though he was and seems barely to have time for them. Their daughter Shinge, owner of a beauty salon, seems even less interested in the company; indeed she appears to be outright resentful of their presence.

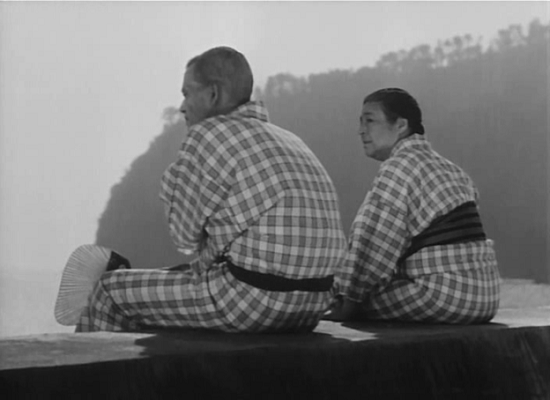

The couple at Atami hot springs resort

Koichi and Shige send their parents to Atami hot springs resort, highly unsuitable for the elderly couple. When they return early to Tokyo, neither Koichi nor Shige is willing to take them in. Only their daughter-in-law, Noriko, a war widow, seem genuinely loving and kind to them; she invites Tomi to stay in her small apartment, while Shukichi must stay at an old friend's. When a drunken Shukichi and his friend are brought to Shige's home by police, the anger and disappointment the parents feel toward their children and children toward their parents send the couple Hirayamas back home.

Shukichi and Tomi visiting their daughter-in-law

On the way home, Tomi is taken ill. A stopover in Osaka to recover for the moment finds the old couple reflecting on their life with a mixture of bitterness and resignation. When Hirayamas return home, Tomi gets worse. Their daughter, Kyoko still living at home, sends for her brothers, sister, and sister-in-law. Shortly after their arrival in Onomichi, Tomi dies. Only Kyoko and Noriko seem genuinely saddened. As Noriko prepares to return to Tokyo, the widowed Shukichi extends his gratitude to her for her love and kindness and urges her to remarry. Noriko's contemplative journey home ends the film.

The old couple with Noriko before departure from Tokyo Station

For the sake of drama, Ozu's films do often hinge around a key life event—usually a marriage or a death. But it's the ordinary moments in between that matter most, the kind of moments left out of most conventional screenplays. Take this bit of dialogue from Tokyo Story: Tomi asks her husband, Shukichi (Chushu Ryu), "I wonder what part of Tokyo we're in?" When he says, "A suburb, I think," she replies, "You must be right. It was such a long ride from the station." That's exactly the kind of mundane banter anyone from any part of the globe could expect hearing their grandparents engage in.

Ozu's appreciation of subtle shades of character means that what isn't said can be more important than what is. When Tomi says, "When each of my boys was born, I prayed that he wouldn't become a drinker," it implies that her husband had in fact a drinking problem, something you wouldn't expect from the ever-so-slightly-stiff Shukichi. Ozu expresses great distinctions in character through the most subtle of differences; Shukichi's daughter Shige very practically packs a funeral kimono when visiting her ailing mother near the end of the film, while his daughter-in-law Noriko comes completely unprepared. It reveals a lot about the different attitudes of the characters, without elevating one over the other.

An intimate moment during Tomi's stay with Noriko

Behind the simplicity of the writing is simplicity in staging and composition that the unschooled eye might see as artless. Ozu usually places his camera no higher than the eye-level of a person sitting on a tatami mat and, almost never moving the frame, records the carefully planned movements and gestures of his actors.

Noriko with Shukichi after the demise of Tomi

By having established the rhythms of Shukichi and Tomi's life together with such precision, Ozu's presentation of the old woman's death, because it's not conventionally melodramatic or histrionic, is all the more deeply felt. When the film ends where it began, with Shukichi sitting on his tatami mat, fanning himself because of the sticky summer heat, this time alone, it's a different presentation of eternity than, say, Dreyer's Ordet. Where Dreyer used resurrection as a metaphor to underline the miracle of life itself, Ozu establishes the miracle of human life by the absence of one life. Though Tomi is gone there will still be the putt-putt of a boat engine in the harbor, the far-off whistle of a train, the endless droning screech of cicadas. And the knowledge that Shukichi and Tomi's children will replace them and one day suffer their fate too. Such is life.

Tokyo story is both intensely insular and immensely universal. Rarely has a film been so immersed in specifics of setting and period, so thoroughly pervaded by the culture in which it was produced. In this exquisite merging of specific and universal, infinite and infinitesimal, Tokyo Story perhaps most clearly illuminates that Ozu is not the most Japanese of filmmakers, but the most human.

A series of "Hundred Favorite Films Forever"

23-Nov-2012

More by : P. G. R. Nair