Feb 16, 2026

Feb 16, 2026

Director: Masaki Kobayashi/Japan/Japanese/128 mts

Samurai Rebellion is an incredible piece of filmmaking. It is as powerful, meditative, and gripping as anything Akira Kurosawa, Kenji Mizoguchi, Yasujiro Ozu, or the other Japanese masters have created. . A daring take on the samurai genre, Samurai Rebellion is packed with social commentary and presses on with gradually building tension and gripping intensity. On a more aesthetic level, the cinematography is dynamic and the choreography crisp. It is one of Toshiro Mifune's finer roles, and is unfortunately a rather obscure title. The film earned him the FIPRESCI Award at the 1967 Venice Film Festival.

In Samurai Rebellion, Kobayashi took his study of the individual against society as far as he could, and enriched it by refusing to restrict himself to the manly world of sword fights. By focusing on family, and particularly on women in family roles, he widened his subject and heightened its emotional potential.

The peace period: Tatewaki Asano (Tatsuya Nakadai) and Isaburo Sasahara

Set during peacetime in 1725, Samurai Rebellion examines the morality and nobility of fading swordsman Isaburo Sasahara (Toshirô Mifune) and his son Yogoro (Takeshi Katô), as they fight their clan’s decision to rob Yogoro of his wife Ichi (Yôko Tsukasa), who had been unceremoniously dumped—exiled, if you will—upon the family for violent misconduct towards their Lord Masakata (Tatsuo Matsumura) only a short time before (Ichi was Masakata’s concubine).

Ichi as wife of the Clan Lord

At the Edo period of Japan, Isaburo Sasahara is a vassal of the daimyo of the Aisu clan. Sasahara is the most skilled swordsman in the land, whose only rival in ability is his good friend Tatewaki Asano (Tatsuya Nakadai). Isaburo is in a loveless marriage with a shrew of a woman Suga. When the film begins Isaburo Sasahara is on the verge of retirement. It's a time of peace, he sees no use for his skills anymore, so he puts his son, son Yogoro (Takeshi Katô) charge of the family and moves on to a quiet life. Enter the clan lord Masakata who ends up ruffling some feathers. Apparently Ichi, the young woman he married had the nerve to strike him when he takes another woman as his mistress and so he orders Yogoro, Isaburo's son, to marry her. Yogoro, in the interest of keeping peace within the clan agrees and Isaburo family (and Yogoro too) is pleasantly surprised when the marriage becomes a happy and loving one.

The Isaburo family with Sugo and other members

Soon the clan lord Masakata changes his mind as his heir dies of pneumonia, Ichi—the woman he dumped on Yogoro and who mothered the next-in-line—is summoned back to take her ‘rightful’ place alongside the Lord. However, Ichi and Yogoro have surprisingly fallen deeply in love, have a baby daughter Tomo, and are horrified at the thought of Ichi going back to the castle. Invigorated by his son’s passion, Isaburo—earlier depicted as a beaten man in many ways—joins the determined couple in making a rebellious stand against the clan’s narrow-minded perspectives, eventually planning to go to Edo and report the clan’s treachery to Japan’s highest powers.

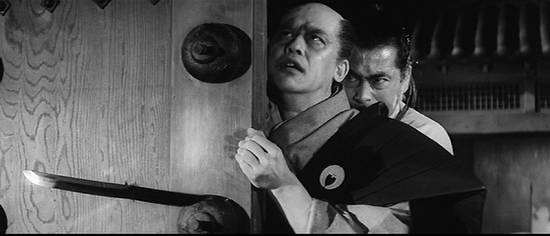

The Samurais of the Clan Lord threaten Isaburo family

The opening of Samurai Rebellion presents a society with conflicted priorities—as Isaburo and his close friend Tatewaki (Tatsuya Nakadai) evaluate the quality of various swords for the Chamberlain, they find themselves mocked for never dueling (Isaburo and Tatewaki are considered the clan’s finest swordsmen) due to concern for their families. It’s evident immediately that Isaburo and the clan don’t see eye-to-eye on what the word ‘family’ represents: to the Chamberlain and Lord, the clan itself must take precedence, what its members should put first. Wives, sons, daughters, and personal friends are little more than secondary insignificances. Conversely, Isaburo—despite being “henpecked” by a verbally abrasive and cold wife in a loveless marriage—has no such illusions. He respects the clan, but puts his blood in the forefront, and doesn’t view the clan’s every word with reverence.

Yogoro and Isaburo confront the Samurais of his clan lord

Though Isaburo is submissive in many ways, we get the instantaneous sensation that something’s about to snap; that Isaburo has great quantities of frustration crying to escape, even if we’ve yet to learn what they stem from. As Samurai Rebellion glides along, we learn the extent of his unhappiness with his wife Suga (Michiko Otsuka), and how much he wants his sons to experience more joy than he. That his other son Bunzo (Tatsuyoshi Ehara) is a weak-willed, spineless jellyfish inspires him to support Yogoro and Ichi’s union until the very end. Indeed, one of Samurai Rebellion’s best sequence features Bunzo as the extended family representative, sent as a messenger to plead for Isaburo and Yogoro’s acquiescence, and unable to say a single word other than “father!” whenever he opens his mouth, as Isaburo calmly verbally undresses him, making it crystal clear that he will not back down from what’s right.

The daimyo's steward, accompanied by his samurais, brings captive Ichi to the Sasahara house

As Samurai Rebellion takes place during a serene time in the countryside, Kobayashi portrays unprovoked feudalistic tendencies: that is, customs and rigid hierarchical structures that aren’t stoked by the fires of battle. Indeed, much of Samurai Rebellion’s story can be viewed as a precursor to war—the selfishness, stubbornness, and frosty relations smack of what ultimately leads to senseless fighting in the first place. Suga’s chilly refusal to accept Ichi into the Sasahara family despite unmistakable, continuous evidence of her beautiful soul; the court’s kamikaze orders without regard to the humanity of others; the family’s refusal to stand by their kin in the face of adversity; all are uncomfortable traits of war-mongering tyrants who like to dub themselves ‘pioneers.’ Kobayashi suggests that even in times of overall tranquility, peace is only a surface reality—there’s always infighting and power-hungry dictators infecting societies that would be otherwise living in harmony.

Volcano of wrath: Isaburo Sasahara (Toshirô Mifune)

Kobayashi utilizes selective tight framing to accentuate the sweat and tension that pervade most of the participants, but never overuses the close-ups; the fluid black-and-white photography is perfect for the simple-yet resonant world that Samurai Rebellion presents. Mifune turns in one his most nuanced performances: during his emotional outbursts—of which there are several, including a showdown with Masakata’s right-hand man and —he emotionally spits out his lines with the same energetic furor as in Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood and Yojimbo, or Hiroshi Inagaki’s Samurai trilogy. However, when he’s quietly lamenting his empty life, appraising his family, or taking stock of the clan’s most recent disloyalty, his face alternately hardens and softens, his voice fills with wistfulness. He’s a truly remarkable actor. The rest of the cast is uniformly outstanding as complements, from Katô as the distraught and fiercely noble Yogoro, to Yokô as the forlorn-but-faithful Ichi, to Otsuka as the unrelentingly aloof Suga.

A critical moment: Isaburo, Ichi and Yogoro

When Isaburo and Tatewaki finally draw swords against each other, it’s for entirely selfless reasons: there’s no crowd to admire their talents, merely their nobility and beliefs in their societal positions and a refusal to conform. If Tatewaki isn’t quite as self-sacrificing as Isaburo throughout—he does, at one point, offer to kill Isaburo in exchange for a major promotion, which he’s refused; it’s unclear if he knew he would be rebuffed, and requested it to avoid having to contest Isaburo, which appears likely—his reasons for blocking the gate and finally fighting Isaburo, as well as for declining the Lord’s initial request to duel, speak for themselves, and inject a much-needed dose of faithfulness into an increasingly somber tale. However: Samurai Rebellion doesn’t end on a happy note—though there’s some reason for optimism—but it’s also not unrelentingly bleak and hopeless. As Isaburo notes, Ichi and Yogoro’s ardor is a superior example of love’s richest powers, and the energy and ideals that it can stir up within. And after you finish absorbing the masterpiece Samurai Rebellion, you just might feel inspired yourself.

The Samurai delivers the last blow to finish off the enemy

Kobayashi directs this film masterfully, pacing it perfectly. It starts off slow, he slowly builds up the tension of the film, but then gives you a breather. He builds it up again, backs it off, and then really ramps up the tension until the last act of the film when Isaburo and Suga finally revolt against their entire clan in a bloody battle.

The actors, specifically Mifune as Isaburo and Yoko Tsukasa as Ichi, are phenomenal. Mifune, if you've seen his work in other films, always brings his acting chops to the table. But Tsukasa is so perfect. She never overacts, and her character's tempered emotions are heartbreaking.

The honor duel: Isaburo and Tatewaki draw swords against each other

The cinematography by Kazuo Yamada is gorgeous. Whether shooting a large, sweeping, panoramic shot, a contemplative medium shot or a tense, emotional close-up, everything looks absolutely perfect. By 1967, most films were shot in color, so the black and white photography looks especially great.

The surprise surrender: Isaburo and Tatewaki

Isaburo Sasahara is indeed one of the great film heroes. The final battle of the film is, like most samurai films, bloody and exciting; and Isasburo is an expert swordsman that kills off many attackers in a climactic scene. But this is not what makes him a great hero. If you get too lost in the action, you'll miss the point. Throughout the film, words like "honor" and "duty" are used by the clan lord and his representatives to bend Isaburo and Suga to their will. They MUST obey. But the "rebellion" of these samurai is not about disrespect or lack of honor. Isaburo realizes his true duty in life is to protect his family, above all else, and everything else is a distant second place.

The final fall: Isaburo Sasahara (Toshirô Mifune)

Sadly, Samurai Rebellion is the kind of movie that doesn't receive the exposure it should. Often it is word-of-mouth that lends to wider audiences for films of this nature, especially nowadays. It appears as though there is a small audience that does comprehend the excellence of this particular piece of cinema, but it is unfortunate that the few there are can't get the message out to other fans.

Samurai Rebellion really should be mentioned right up there with Kurosawa's greats. Fortunately, for those who have discovered what this movie has to offer, they know full well what others are missing. Samurai Rebellion is a paradigm of social commentary in the samurai genre, a brilliant epic with a message about love, dissent, and justice.

A series of "Hundred Favorite Films Forever"

15-Dec-2012

More by : P. G. R. Nair