|

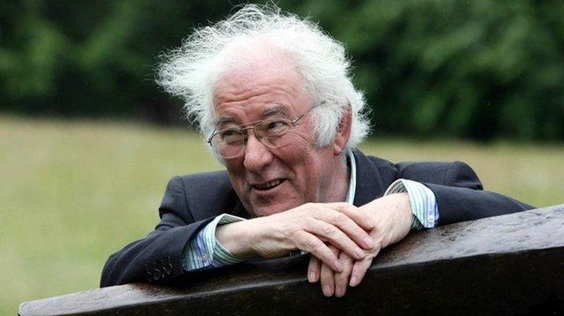

Homage to Seamus Heaney (1939-2013)

Seamus Heaney, Ireland’s foremost poet who won the 1995 Nobel Prize for Literature ‘for works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday miracles and the living past’, died on Friday, August 30 . As the greatest Irish poet of his generation, he never lost his instinctive feel for the universal rhythms of rural life, his ability to see the extraordinary in the humblest of places, and to express it with an eloquence and beauty in his poetry that could make the reader’s heart stand still.

Seamus Heaney will also be remembered for his translation and for his literary essays. His lyric translation of “Beowulf” made the Old English epic poem a bestseller in 2000 and introduced the history of the English language to scores of School children. Another great translation venture he undertook along with Stanislaw Baranczak was the translation of the 16th century Polish poet Jan Kochanowski’s “Laments”.

Mr. Heaney made his reputation with his debut volume, “Death of a Naturalist,” published in 1966. In his famous poem “Digging,” he explored the earthy roots of his art and wrote:

“Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests; snug as a gun.”

Since the poet hailed from a farming community engaged in digging fields for cultivation, ‘Digging’ establishes the poet’s most significant and versatile metaphor for the creative endeavor and the search for truth – digging. The metaphor is multi-faceted and capable of simultaneously embracing seemingly contradictory notions. While it is healthy to loosen the soil to plant and harvest, to dig into one’s psychic past, to explore one’s history through archaeology, mythology and etymology, it can also be painful and destructive. On the surface ‘Digging’ examines the natural longing for familial and communal continuity – my ancestors worked the land, so I should work the land – while acknowledging that the very awareness of the past results in an increased consciousness that separates the poet from it and its comforts.

Seamus Heaney was also one who believed it was the role of the artist to give a voice to those who were oppressed and ignored, who never saw a boundary between art and compassion, but rather believed that art was fundamentally driven by empathy, by a bond that links every living person.

I wish to examine here some of the poems of Heaney that have held personal appeal to me. I had written earlier in Boloji a literary appreciation of his famous poem “Blackberry Picking” . It was my first introduction to his great poetry. The image of children hurrying to pick more and more blackberries and later facing the disappointment of finding it rotten with fungus speaks about the half-innocent greed of the blackberry-pickers.

Let us begin with a deeply touching and tender poem that reminisces the narrator's mother titled ‘Clearances iii’.

Clearances iii

(In Memoriam M.K.H., 1911-1984)

When all the others were away at Mass When all the others were away at Mass

I was all hers as we peeled potatoes.

They broke the silence, let fall one by one

Like solder weeping off the soldering iron:

Cold comforts set between us, things to share

Gleaming in a bucket of clean water.

And again let fall. Little pleasant splashes

From each other’s work would bring us to our senses.

So while the parish priest at her bedside

Went hammer and tongs at the prayers for the dying

And some were responding and some crying

I remembered her head bent towards my head,

Her breath in mine, our fluent dipping knives –

Never closer the whole rest of our lives.

The above wonderful poem taken from ‘Clearances’ is dedicated to his mother, Mary Heaney, who died in 1984. The poem describes the close relationship between Seamus Heaney and his mother. The octave (first 8 lines) of the sonnet describes a past incident between the mother and the child. In this past scene, the mother and her child are working in the kitchen, peeling potatoes. They work in silence. They are so engrossed in each other’s company that they are brought back to their senses only by the little splashes made by the potatoes falling one by one into a bucket of water like “Solder weeping off the soldering iron.”

The atmosphere that the poem evokes is one of isolation and silence. The life in that household was perhaps not one of acceptance and happiness for this mother and child. All the others having gone to church and the poet as a child is left alone in the house with his hard-working mother, preparing the Sunday lunch ‘while the others were all away at mass.’ He says, ‘I was all hers’, but we can tell that what he really means is, that she was all his. In the silence, their knives dip in and out of the water, the two doing a sort of dance together.

The sestet (rest six lines) represents the present: we are brought to the dying mother’s bedside. The parish priest beats out his prayers for the dying in a loud voice, but obviously without any real emotion. The other people gathered there are the dying woman’s relations and friends. Some of them say ‘Amen’ and some are crying, but none of them appear to feel as deeply as the narrator does about her. While the others are thus feigning grief, the son or the narrator who is genuinely overwhelmed by sorrow on the occasion stands in silence. The present scene reminds the narrator of the days when he shared moments of deep intimacy with his mother peeling potatoes. The mother and the child experienced a kind of mutual devotion in that silence. Yet, the dipping knives were ‘fluent’: the cold dipping knives are paradoxically expressive of the warmth of the love between the mother and the son. The rhyming couplet brings the experience to a satisfactory close.

It is the silence of that lost moment that the poet recalls at her deathbed and he feels he has never been closest to his mother as when they were peeling potatoes. It is appropriate that Heaney uses the most Irish of vegetables, the humble potato, that binds this silent Irish boy and his mother so closely together; the ‘potato’ and the ‘water’ being so symbolic of domestic Irish life.

This poem is thus about a loving mother-child relationship sustained in an unsympathetic environment. Even at the death of the woman, while the others remain indifferent and unloving as usual, the son keeps alive this special relationship in an atmosphere of profound sadness.

The Poem “Mid-Term Break” is so fabulously composed and suspended that its ordering, its empathies, its sense of emotional time and lyric timing, and its ability to create restrained intimacy in the face of trauma are perhaps unmatched. Concerned with the death of the poet’s younger brother, Seamus Heaney’s “Mid-Term Break” is a sustained, poignant utterance. It has aplomb and coolness. It has presence of mind and nerve. It has deportment and it has horror. It has finally, in a word, poise.

“Mid-Term Break”

I sat all morning in the college sick bay

Counting bells knelling classes to a close.

At two o’clock our neighbors drove me home.

In the porch I met my father crying −

He had always taken funerals in his stride−

And Big Jim Evans saying it was a hard blow.

The baby cooed and laughed and rocked the pram

When I came in, and I was embarrassed

By old men standing up to shake my hand

And tell me they were ‘sorry for my trouble,’

Whispers informed strangers I was the eldest,

Away at school, as my mother held my hand

In hers and coughed out angry tearless sighs.

At ten o’clock the ambulance arrived

With the corpse, stanched and bandaged by the nurses.

Next morning I went up into the room. Snowdrops

And candles soothed the bedside; I saw him

For the first time in six weeks. Paler now,

Wearing a poppy bruise on his left temple,

He lay in the four foot box as in his cot.

No gaudy scars, the bumper knocked him clear.

A four foot box, a foot for every year.

Though one of his first published poems, “Mid Term Break” shows a remarkable degree of poetic maturity and control, dealing as it does with death of one his younger brothers, the four year old Christopher. Isolated from the rest of the school in ‘in college sick bay’ − as if death itself might be contagious − the boy listens to the “bells knelling classes to a close” , the knelling conveying a premonition of death.

The familiarity, predictability of home, however, is immediately violated by the sight of his crying father and the sound of his mother’s ‘angry tearless sighs’. Once more Heaney is deft and delicate in handling the double perspective, the reader being simultaneously aware of child’s embarrassment in suddenly becoming the focus of stranger’s sympathy, and the adult writer’s irony describing the contrasting emotion of how the baby of the family, unaware of the happenings, ‘cooed and laughed and rocked the pram’.

After the inadequate stock phrases proffered by the community-understatements that cannot bear grief-the poet chooses the opposite images to move us. The snowdrops and the candle imply innocence and fragile beauty, qualities reiterated when Heaney talks metaphorically of “poppy bruise on his left temple'”, poppies being the colour of blood as well as a symbol of the dead. Heaney uses the word ‘box’ rather than coffin, and the poet feels as if the child still slept in his cot.

The mathematical preciseness, the tragic equation within the final line − “A four foot box, a foot for every year” − deepen the pathos of the poem's ending.

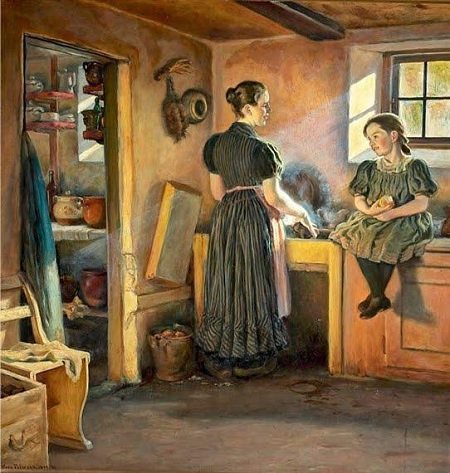

The ‘Sunlight’ is often cited as one his best poems and can be found in many anthologies.

Sunlight

There was a sunlit absence.

The helmeted pump in the yard

heated its iron,

water honeyed

in the slung bucket

and the sun stood

like a griddle cooling

against the wall

of each long afternoon.

So, her hands scuffled

over the backboard,

the reddening stove

sent its plaque of heat

against her where she stood

in a floury apron

by the window

Now she dusts the board

with a goose’s wing,

now sits, broad-lapped,

with whitened nails

and measling shins:

here is a space

again, the scone rising

to the tick of two clocks.

And here is love

like a tinsmith’s scoop

sunk past its gleam

in the meal-bin.

In the above wonderful poem ‘Sunlight’, the speaker is standing in the kitchen with his aunt. It opens with a mystery, with the illumination of an ‘absence’. The vacancy, however, is quickly filled by one and then two substantial family ‘personalities’ to which image of light, heat and sweetness accrue. The pump, like its human counterpart, Heaney’s Aunt Mary, is realized in the poem as physical and mythical entity. The adjective, ‘helmeted’, which initially describes it, suggests not only its shape and its human attributes, but also establishes its role as guardian of the territory. It embodies cast-iron reality, occupies, literally, a concrete place, yet also serves as a symbol or icon for subterranean energies of the place and its people. Through the intercession of the sun, it participates in a miracle, as water collected in the occasionally ‘slung bucket’ undergoes transubstantiation. To a child’s eyes, even the immensity of the sun can be contained and domesticated, and Time itself can seem to stretch. The sun’s huge heat is made comparable to a ‘griddle’, the words, like ‘pump’, ‘stove’, ‘goose’s wing’, ‘tinsmith’s scoop’, ‘meal-bin’ calling to mind an earlier age. It also serves to smooth the move from outside to inside of the house, from a wall of warmth to a ‘plaque of heat’, and towards the principal figure of the poem, Mary Haeney, busy at baking.

As can be seen, in 17th line, the poem suddenly moves from the Poet’s memory to the real presence of his aunt captured in the present tense (‘Now she dusts the board’). In the kitchen, the speaker’s aunt is preparing to bake bread for her family members. Her hands are moving over the bake board. She is standing near the window. Her apron is covered with flour. The stove is red-hot and because of the summer its heat could be felt even at the window. She cleans the flour on the bake board with the wing of a goose. She then sits making her lap wide. The flour has made her nails white and one can see the spots on the front part of her lower legs. Because of the mother’s presence, the kitchen has become a lovely place where one can move or breathe.

Her presence is made immediate to us by use of many visual, sensual details (‘floury apron’, ‘whitened nail’, ‘measling shins’) and verbs emphasizing her alternating bursts of activity and passivity (‘scuffed’, ‘stood’, ‘dusts’, ‘sits’). Heaney’s pleasure in recollection energizes the short enjambed lines, whose momentum is unchecked until a second space appears in line 22. As with the original ‘sunlit absence’, the poet experiences a sense of fullness, not of loss. As the poet says, “Here is space again”. These “full spaces” or moments occurring in empty and dry spaces have a power to resacralize a world .

Aunt and nephew, baker and writer, pauses to allow the yeast to rise in the scones and the poem. Each in their act of making affirm kinship and the depth of family feeling. Despite the tarnishing of time, their love, like ‘tinsmith's scoop’ , is tangibly ‘here’ in the present tense and retains its gleam.

The below passage from his poem “North” contains probably the best advice anyone could give to an aspirant poet.

“It said, ‘Lie down

In the word-hoard, burrow

The coil and gleam

Of your furrowed brain.

Compose in darkness.

Expect aurora borealis

In the long foray

But no cascade of light.

Keep your eye clear

As the bleb of the icicle,

Trust the feel of what nubbed treasure

Your hands have known.’”

Its counseling voice speaks to him across 1200 years of time, about literary enterprise, language, the poetic process, the artistic temperament and personal integrity. It advises us to be at one with one's own linguistic resources (Word-hoard here refers to the hidden treasures (vocabulary, shades of meaning) stored in the writer’s mind), delve deeply and concentrate within the coil and gleam of your furrowed brain; reconcile oneself to composing in darkness; anticipate the discrete shimmer of composition, an aurora borealis than a starburst: no cascade of light; accept that what one undertakes will require stamina and commitment as for a long foray (like Viking explorations); keep the mind lucid and on task ; one's eyes as clear as the bleb (meaning swelling or bubble) of the icicle.

Heaney's fidelity to his difficult vocation, his command to ‘compose in darkness’, to work without the comfort even of hope for a ‘cascade of light’, and yet to be faithful witness to whatever gleans are there, is absolute and awe-inspiring, both in this poem and those that follow. Even in the poems whose dominant imagery is darkness, cold and exposure, Heaney never loses this calling to clarity. The poet’s eye, and -through the exercise of the imagination, and therefore clear enough to see when the icicle melts, ‘the diamond absolutes’ caught in a falling drop.

As Michael Parker says, “In ‘North’, the vocation to compose in darkness had been understood both in terms of the monastic vision of ‘Gallurus Oratory’, and of the heroic age when fili, the early Irish poets, were expected to go into darkness and retreat to compose.”

Heaney’s poems have a rare auditory quality. His focus on sound in his poetry is a natural progression from his vowel-rich South Derry dialect and vocabulary. His stanzas are dense echo chambers of contending nuances and ricocheting sounds. And his is the gift of saying something extraordinary while, line by line, conveying a sense that this is something an ordinary person might actually say. Heaney chooses his words very carefully and effectively which make his words appeal to the senses, thus creating in the mind of the reader a mental picture true to the poet’s intention.

Reading even the new poems aloud gives you the sense of almost chewing on the lush syllables. “Hazel stealth. A trickle in the culvert./ Athletic sea-light on the doorstep slab,/ On the sea itself, on silent roofs and gables.” The word sounds are a musical accompaniment to the imagery. He says about it in an interview:

“But this isn’t peculiar to me. This belongs to the language. I think everybody, whether or not they’re conscious of it, responds to these things, you know ... that sound carries something more with it within any signaling structure within the English language collective. We have certain associations with certain sounds. And so what a poet is doing is unconsciously working with that. I am very devoted to T. S. Eliot’s notion of the “auditory imagination.” ... Eliot talks about the feeling for syllable and rhythm reaching below the conscious levels. You're adding the most ancient and most civilized mentality.”

As a person, Seamus Heaney possessed that rare quality of being acclaimed and loved by people from all backgrounds and from all parts of the world. Despite his fame he remained modest and down to earth, and became even more endearing because of this. In a 1997 interview in The Paris Review, Mr. Heaney described winning the Nobel as “a bit like being caught in a mostly benign avalanche. You are totally daunted, of course, when you think of previous writers who received the prize. And daunted when you think of the ones who didn’t receive it.” He was also a poet of immense dignity, effusive to his readers and a well of inspiration to his fellow poets. He never cast aspersions on anyone he had come across, including his critics.

Seamus once confessed that he saw poetry as an escape from a terrible fear of silence that always haunted him. “What is the source of our first suffering?” he asked, quoting the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard. “It lies in the fact that we hesitated to speak.” It is gratifying that the poet, who died Friday at the age of 74, mastered that fear magnificently in five decades of lyrical compositions dwelling on “the silent things within us” and became one of the greatest poets of this century.

References:

Opened Ground: Selected Poems, 1966-1996 by Seamus Heaney

Seamus Heaney : The Making of a poet by Michael Parker

Seamus Heaney : Helen Hennessy Vendler

Poems, 1965-1975: Death of a Naturalist / Door Into the Dark / Wintering Out / North by Seamus Heaney |