|

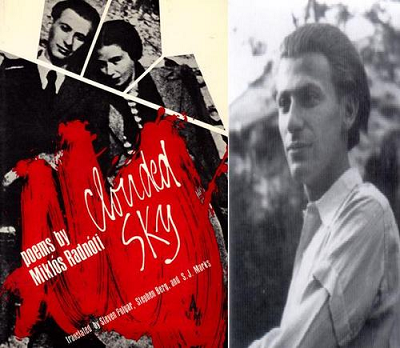

Miklos Radnoti (1909-1944), the Hungarian Jewish poet and a fierce anti-fascist, is considered as the greatest of the Holocaust poets. His poetry collection, “Clouded Sky”, wonderfully translated by Steven Polgar, Stephen Berg, and S.J. Marks, alone is enough to rank him as a truly great poet , one in whom the lyrical image-maker and the critical human intelligence find a perfect fusion. Miklos Radnoti (1909-1944), the Hungarian Jewish poet and a fierce anti-fascist, is considered as the greatest of the Holocaust poets. His poetry collection, “Clouded Sky”, wonderfully translated by Steven Polgar, Stephen Berg, and S.J. Marks, alone is enough to rank him as a truly great poet , one in whom the lyrical image-maker and the critical human intelligence find a perfect fusion.

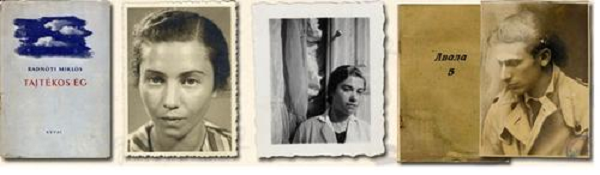

Before discussing his poems, I will condense his biography in a few words. Born in 1909, Radnoti emerged as a promising lyricist in the artist circles of Budapest in the early 1930s. In 1935, Radnoti married his childhood sweetheart, Fanni Gyarmati, hoping to secure a teaching position in the Hungarian high school system. When this did not work out, he took temporary jobs, chiefly private tutoring, and accepted partial support from his wife’s family.

As Hungary’s political climate turned increasingly fascist, Radnoti shared the fate of those who had been persecuted for their Jewish origins. With the exception of brief periods of respite, he spent the years from 1940 until his death in various forced-labor camps. In May 1944, two months after the German occupation of Hungary by the Nazis , Radnoti was forced into a Jewish labor battalion to build roads in Yougoslavia. During the fall of that year, the Germans evacuated the Balkans and ordered the exhausted, emaciated servicemen to march back to Hungary and then through to Austria. When Radnoti could walk no longer, he was shot in the neck by his Hungarian Guards and buried, together with twenty-one of his comrades, in a mass grave near the village of Abda in western Hungary.

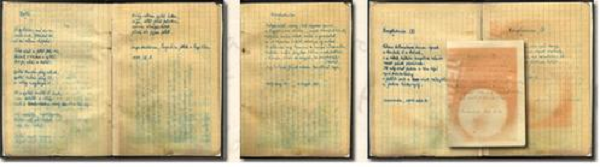

When the grave was discovered and his body was exhumed on June 23, 1946, nearly two years after his death, his wife found a small, black notebook of ten poems in the pocket of his raincoat which he had written during his years in the work camps. Rising from the grave, these poems have come to occupy an extraordinary place in twentieth-century literature; they not only manifest great beauty, exceptional range and masterful designs, but also record one of the most brutal mass murders in history. This poetry collection contains all the famous poems from that notebook including ‘Forced March” and “Postcard”.

Let us now move into some his celebrated poems.

I Don’t Know

I don’t know what this land means to others, this little country

Fenced in by fire, place of my birth,

world of my childhood, swaying in the distance.

I grew out of her like the young branch of tree,

and I hope my body will sink down in her.

Here, I‘m at home. When one by one, bushes kneel at my feet,

I know their names and names of their flowers.

I know people who walk the roads and where they’re going

and on a summer evening, I know the meaning of the pain

that turns red and trickles down the walls of the houses.

This land is only a map for the pilot who flies over.

He doesn’t know where the poet Vorosmarty lived.

For him factories and angry barracks can’t be seen on this map.

For me there are grasshoppers, oxen, church steeples, gentle farms.

Through binoculars, he sees factories and plowed fields:

I see worker, shaking, afraid for his work.

I see forests, orchards vibrant with song, vineyards, graveyards,

and wizened old woman who quietly weeps and weeps among

the graves.

The Industrial plant and the railway must be destroyed.

But it’s only a watchman’s box and the man stands outside

sending messages with a red flag. There are children around him,

In the factory yard a sheep dog plays, rolling on the ground.

And there’s the park and the footprints of lovers from the past.

Sometimes kisses tasted like honey, sometimes like blackberries.

I didn’t want to take a test one day, so on my way to school

I tripped on a stone at the edge of the sidewalk.

Here is the stone, but from up there it can’t be seen.

There’s no instrument to show any of it.

Among Radnoti’s images, a few run throughout his works as recurring metaphors and symbols. He uses the figure of the pilot, for example in the above poem, as an embodiment of the insensibility chillingly evident in war. The pilot becomes in this one a symbol of all willing instruments in the service of inhumanity; his actions derive from a worldview in which separation leads to indifference. When sufficient distance is created between malefactor and victim, the wrongdoer ceases to feel any guilt concerning his crime. In this poem “I don’t Know”, Radnoti pits the humanist’s values against those of the pilot. It is a poem about Hungary as seen, on one hand, by a native son, the poet, and, on the other hand, by the pilot of a bomber plane from another country. The poet sees his “tiny land” on a human scale:

“In the factory yard a sheep dog plays, rolling on the ground.

And there’s the park and the footprints of lovers from the past.

Sometimes kisses tasted like honey, sometimes like blackberries.

I didn’t want to take a test one day, so on my way to school

I tripped on a stone at the edge of the sidewalk”

To the man in the plane, however, “This land is only a map for the pilot who flies over. He doesn’t know where the poet Vorosmarty lived.” The pilot sees only military targets such as army barracks, factories etc—while the poet sees “grasshoppers, oxen, church steeples, gentle farms.”

This poem wonderfully proclaims the true feelings of a universal poet whose heart beats with the flora and fauna around him.

The last poems of Radnoti, written under the pressure of the most degrading and desperate circumstances imaginable, unfurl visions of delicate pastoral beauty next to images of extreme degradation and wild, filthy despair. They give voice to the last vestiges of hope, as Radnóti fantasizes being home once more with his beloved Fanny, as well as to the grim premonition of his own fate. This impossibly stark contrast blossoms into paradox: Radnóti’s poetry embraces humanity and inhumanity with an urgent desire to bear witness to both.

Yet even at the moment when he is most certain of his imminent death, he never abandons the condensed and intricate language of his poetry. And pushed to the limits of human endurance and sanity, he never loses his capacity for empathy. This is what is evident in the poems, “ Forced March” and “Postcard”.

Forced March

You’re crazy. You fall down, stand up and walk again,

your ankles and your knees move

but you start again as if you had wings.

The ditch calls you, but it’s no use you’re afraid to stay,

And if someone asks why, maybe you turn around and say

that a woman and a sane death a better death wait for you.

But you’re crazy. For a long time

only the burned wind spins above the houses at home,

Walls lie on their backs, plum trees are broken

and the angry night is thick with fear.

Oh, if I could believe that everything valuable

is only inside me now that there’s still home to go back to.

If only there were! And just as before bees drone peacefully

on the cool veranda, plum preserves turn cold

and over sleepy gardens quietly, the end of summer bathes in

the sun

Among the leaves the fruit swing naked

And in front of the rust-brown hedge blond Fanny waits for me,

The morning writes slow shadows—

All this could happen The moon is so round today!

Don’t walk past me, friend. Yell, and I’ll stand again!

(Breaks in each line as given in the text)

The poem begins with a judgmental view of the poet, observed in the third person. Radnoti admits in the first line that he is “crazy”, which is understandable given the barbarous conditions of the forced March. This “craziness”, sense of a man losing his mind, comes across in the surreal lines, “Only the burned wind spins….above houses at home,/Walls lie on their backs,…plum trees are broken”.

When Radnoti falls down on the March, he is somehow able to ‘stand and walk again’. as if he had ‘wings’. He refuses to die in the roadside ditch , because “a woman and a sane death…a better death “ await. He feels that he is crazy, and that “the angry night …is thick with fear”, yet the thought that “there’s still home to go back to”, that blond Fanny awaits” urges him forward. “All this could happen”, he tells us , “don’t walk past me, friend…Yell, I will stand again!”, reminding them to be alert on him.

Halfway through the poem, a sudden transformation occurs, a shift from the third person to the first. Judgment turns into a confession of hope, the war-torn landscape is transmuted into an idyll of bygone days, dogged resistance into a cosmic, optimistic message. In a world from which reason has disappeared, anything, including superstition and magic, can serve as crutches.

In this unique poem , Radnoti employed long breaks between words in order to create the visual image of half-starved soldiers marching on. With the exception of the second line of the poem, each line is broken by a caesura ( meaning a blank space as a pause or interruption ) , which seems to relay the stop-and –go, zombie –like shuffle of someone on a forced march, as if the poet is imparting not only the weariness of his mind and soul, but his actual physical status with the rhythm of his words and lines. This is quite extraordinary whether the poet intended it or not.

Although he had long been prepared for death, Radnóti paradoxically regained a hope for survival during the last bitter weeks of his life. The wish to live, to return to Fanni, his wife, to tell about the horrors, and to wait for a “sane.. better death” permeates several of his poems . Well aware that this hope was flimsy at best, based on desire more than on truth, Radnóti expressed its elusiveness at his best in “Forced March.”

Literature offers number of poems written by Holocaust survivors or others who faced the atrocities of modern warfare. But this one has a ring of truth -- of memory unvarnished by the passage of time. I am particularly moved by how the poet conveys the way a person's mind wanders to happier times and almost loses touch with the horrors of the present in the second half of the poem, and then is yanked back into the on-going atrocity by the fear of falling behind.

“Forced March” impresses and moves the reader with its spontaneity, its simple vocabulary and familiar imagery and its emotional directness. It is the last cry for survival. This poem has a special place in Radnoti’s oeuvre: It represents hope’s triumph over despair. Above all, it shows the artist’s triumph over his own fate. It proves that even during the last weeks of his tormented life, Radnoti was able to compose with precise poetic principles in mind, that he was in control of his material, playing secretly with literary and existential relationships and creating out of all this an enduring testament.

It is appropriate to post here an unabashedly sentimental, and yet beautiful, love poem he had written prior to 'Forced March'. It intensely expresses his unfulfilled desire to be in the arms of Fanni.

In your Arms

I sleep in your arms,

it's quiet.

You sleep in my arms,

it's quiet.

I'm a child in your arms

who is silent.

You are a child in my arms

I listen.

You hold me in your arms when I'm afraid.

I hold you in my arms.

I'm not afraid.

In your arms even the great silence

of death can't

scare me

In your arms I'll

survive death.

It's a dream.

Let us now examine the poem, “Postcard”. This poem is breathtaking, luminous and pared down to exquisite precision even though he was writing it under barbaric and inhumane conditions.

(Recovered notebook of radnoti)

Post Card

I fell next to him. His body rolled over.

It was tight as a violin string before it snaps.

Shot in the back of the head—"This is how

You’ll end". "Just lie quietly", I said to myself.

Patience flowers into death now.

"Der springt noch auf", I heard above me.

Dark filthy blood was drying on my ear.

Life is snuffed out in this poem. Radnoti speaks to the unspeakable in these seven lines, to the horrific death he knew was coming. The poem inscribes a suffering unimaginably intense, a consciousness of death unbearably palpable. The poem was written on October 31 1944 and on Nov 6th the poet was shot and tossed into a collective grave.

It seems as if the poem itself rose from the mass grave as a final testament to the fate of all those who perished. By titling the poem as 'Postcard', probably the poet wanted to condense his life into that of a postcard, which is often characterized as much by what is left out as by what is put in, and its brevity speaks volumes to what must be left unsaid. There is a terrifying stoicism to the line "Patience flowers into death now". A blossoming into oblivion. Then he hears an unattributed voice floating over him in German, the language of death.

In his essay, American poet Edward Hirsch mentions that the German phrase "Der springt noch auf" means something like "Wait till you see this guy break open". The verb 'aufspringen' , which means to "to break or pop open" , is usually used to describe a bud or flower. It's an image of germination , and so perhaps there's a hidden tenderness here, as if the poet ventriloquized the German to say, "Wait till you see him blossom." He is breaking free of his fetters; and death has become a liberation. The last sentence "Dark filthy blood was drying on my ear" has an eerie calmness. The poet is thinking associatively here and the line stuns as the one who listens and observes is still alive, speaking from earth.

This is the greatest holocaust poem I have ever read. It has the moonglow of a poem made halfway to Hades.

Radnoti is one unique poet whose work has irreversibly become one with his life and tragic death . There is no divide between his life and work, they continue to exist in an interplay, mutually interpreting one another. It is my firm belief that the story of Radnoti’s life, his love, his courage, the crystal-clear tone of his poems written in the great lyrical tradition documenting the tears of a deplorable phase in human history will last another millennia as they are of supreme significance in the saga of our civilization.

References:

(1) In The Footsteps Of The Orpheus: Life And Times Of Miklos Radnoti by Zsuzsanna Ozsvath

(2) Clouded Sky: Poems by Miklos Radnoti translated by Steven Polgar, Stephen Berg, and S.J.Marks

(3) How to read a poem: Edward Hirsch

|